No products in the cart.

- 12 Minute Read

Every red-blooded 20th-century American boy at some point wanted to be a cowboy. It was an unspoken rite of passage.

Somehow someway someone eventually exposed us to a western and when our imaginations seized that moment playtime was never the same.

For myself and my brother, that moment occurred when our father decided that we were old enough—ages 7 and 3, respectively—to watch the 1985 Lawrence Kasdan film Silverado. Movies took longer to reach home video in those days, so we didn’t see it until ’87-ish, but all it took was for the opening credits scene to play out for us to be hooked: 16 shots fired and three dead bad guys in the first two minutes commanded our full attention!

Although, the moment that truly cemented itself in our imaginations was when Kevin Costner’s young and rowdy character Jake slowly backs out of a saloon as two characters hunting him slowly stalk away: one to the left, the other to the right.

“Hey!” Jakes shouts, staring straight ahead into the saloon, and, as they turn, he draws both of his pistols and shoots them simultaneously—without looking.

For weeks afterward, our near-daily obsession was finding two sticks of roughly the same size and shape that could double for pistols as we played out that scene in the front yard over and over and over: “Hey!—Bang, bang!”

The TV movie Desperado starring Alex McArthur as Duell McCall followed soon after, along with its four sequels, and for at least two decades I could never hear the opening chords of The Eagles’ song “Desperado” without also visualizing the opening credits of the series.

From there we discovered The Man From Snowy River, Jeremiah Johnson, and the rapturous magnificence of Sergio Leone’s spaghetti westerns starring Clint Eastwood.

Then, at some point, along about fourth grade, my father placed a book in my hand, “Here, read this, boy.”

On its cover, in bold letters over a painted western action scene, was blazoned the name Louis L’Amour. For the life of me I can’t remember its title, but I do remember struggling to read it, both because it was advanced for my age and because I remember it being a straight-forward shoot-’em-up, which didn’t much capture my imagination at the time. When relaying this information to my father, he—as if somehow divining what my imagination craved—said, “Here, this one has an Indian medicine man with mystical powers,” as he handed me The Californios. I struggled to read that one, too, but I had to know all about this medicine man and his mystical powers, so I persevered—and my imagination was lit on fire.

After that, “They hunt woolly mammoths in this one,” he said handing me Jubal Sackett. It, too, was a struggle to read, but I had to know all about this woolly mammoth hunting—imagination firing on all cylinders.

Around this time is when I remember first seeing the name Zane Grey and correlating his books with L’Amour’s because his covers also featured his name blazoned over painted western scenes.

“Who’s Zane Grey?” I asked my father.

“He’s a writer, like Louis L’Amour,” he said.

“Do you like his books?”

“Meh. . . .” my father answered, shrugging, indicating he didn’t like Grey as much as L’Amour. “He’s from Zanesville, you know,” he added.

“Really?!” I found this news enthralling because Zanesville was only a two-hour drive from where we lived at the time.

That proximity spurred me to read whichever Grey book it was whose cover had caught my eye, but I eventually bailed on the story when I discovered how “wordy” it was. L’Amour was already a challenge for my fourth-grade eyes so that Grey book seemed light years ahead. And that was how my relationship with Grey stood for several years: Louis L’Amour, but wordier.

Flash forward to ninth grade. The details of what this reading program was about, exactly, have faded from my memory, but at the beginning of the school year we were given some sort of assessment test in Reading class with the results being that those students who scored the highest were granted the privilege to sit at the back of the classroom and read books all year. Astonishingly (to me, at least), I was one of the four highest-scoring students.

“I can read whatever I want?” I asked incredulously.

“Yes, whatever you want, but afterward you must take a quiz to prove that you’ve read it,” my teacher answered.

And so I proceeded to sit at the back of the class—wondering how this program was fair to the rest of the students who eyed us four enviously—and read Louis L’Amour books, one after the other. Comstock Lode, The Cherokee Trail, The Rustlers of West Fork, High Lonesome, The Iron Marshall, The Man From Broken Hills, and others. I even reread The Californios and Jubal Sackett.

“Can’t you read something other than Louis L’Amour books?” my teacher asked mid-semester.

“But you said I could read whatever I want.” I reminded her.

“Well, yes, you can, but you need some variety. I mean, if it must be a western, then read Zane Grey, too, at least,” she pleaded.

So I went to the school library and checked out a Grey book, then promptly gave up on it having reached the same conclusion as before—Louis L’Amour, but wordier—and resumed my marathon de L’Amour.

At some point, however, my teacher must have threatened me because I remember reading Animal Farm, Lord of the Flies, and Robinson Crusoe.

I must have read others, but I mostly only remember Louis L’Amour that year—which probably explains why I haven’t read any of his novels since.

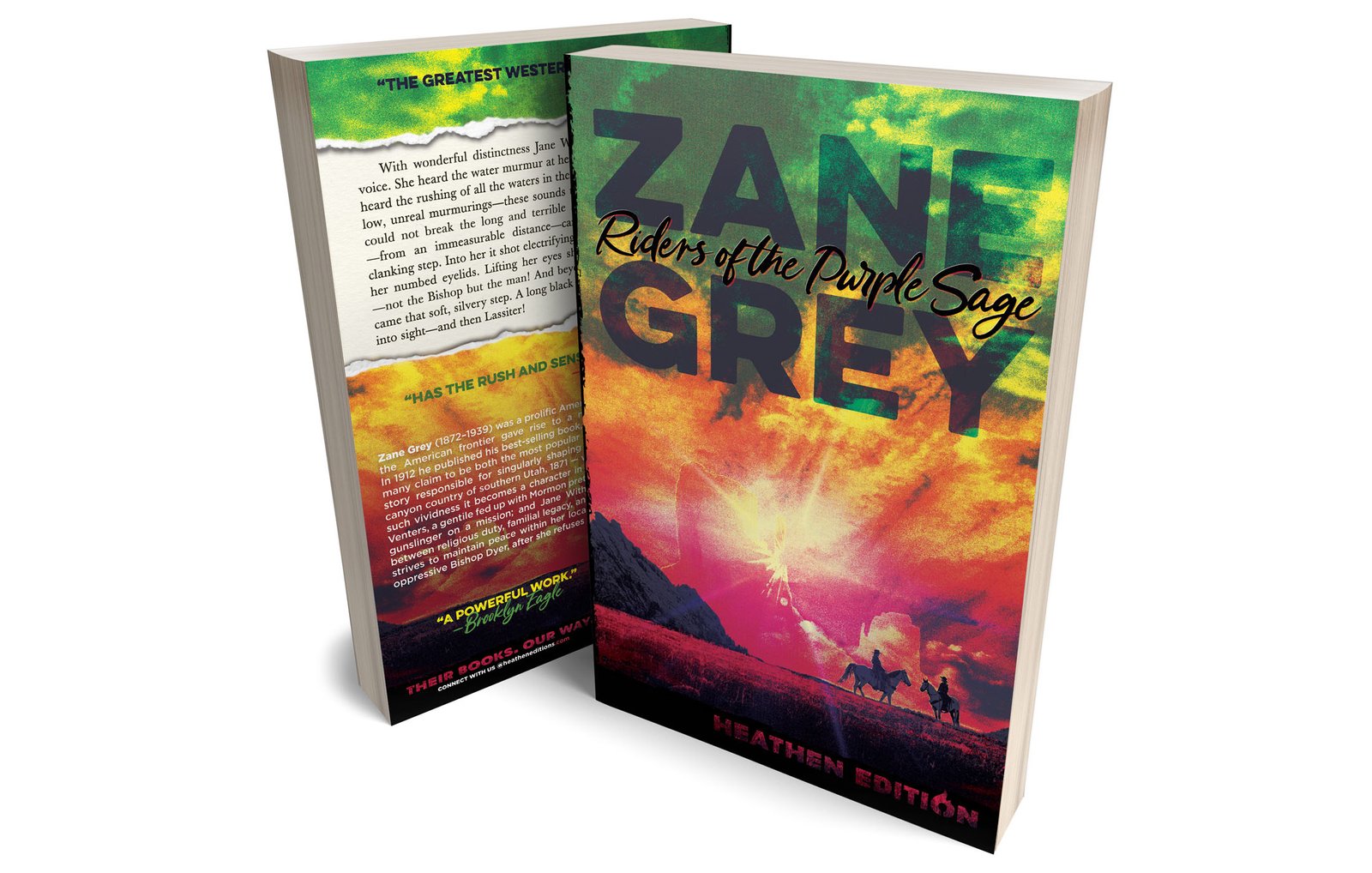

Flash forward to the present, and as I looked over all of the Heathen Editions that we’ve published so far and the ever-growing list of ones that we have earmarked for the future, I realized there wasn’t a single western in sight, which immediately struck me as near-sacrilege given our western-loving roots. “Hey!—Bang, bang!”

Is it time to give Grey another chance? I thought. My mind immediately leaping to Grey, likely because I had given up on him twice. Third time’s a charm, perhaps?

The only question when looking at his 89-book (!) bibliography was where to begin. I was aware that Riders of the Purple Sage was his most popular and best-selling book, so I reread that synopsis and oof . . . Mormons I thought, my fear being that the story’s antagonists were the bad guys because they were Mormon and, deciding that that was a rocky road I surely didn’t want to travel, I went back to the bibliography and continued searching.

You know those scenes in movies where the character does something, then leaves the frame but the camera remains stationary, then a moment later the character reappears? That’s what happened in my mind.

I suddenly went back to Riders and reasoned Hold on, if this is his most popular and best-selling book, then I’ve jumped to a conclusion based on that synopsis. There’s gotta be more to this. All right, Mr. Grey, it’s time. . . .

The result? Well, had I bailed a third time, you certainly wouldn’t now be reading this! I did jump to a conclusion, and my fear was unfounded: the antagonists aren’t bad guys because they’re Mormon, they’re bad guys who claim to be Mormon in order to perpetrate their dastardly schemes—their actions reveal their true nature—a nature brought into sharp contrast when compared to the loving actions of the story’s Mormon protagonist Jane Withersteen.

Said another way, and without spoiling anything, Grey was smart about his commentary on Mormonism: he could shine a light on the dark side of the religion by way of and through his guiding light Miss Withersteen, since she so wholly embodies the Holy instruction “Do unto others. . .” While the antagonists, Bishop Dyer and Elder Tull, flaunt their Holy pretensions in order to exact personal gain—a cancer that is, I believe we can all agree, present in every religion.

And I wasn’t entirely wrong about Grey’s “wordiness.” He’s definitely wordy, but I now realize that, before, I couldn’t fully appreciate how Grey paints a scene for you. While reading and rereading this story, I was particularly awed by the scene in Chapter 13 in which Venters and Bess experience the approach of a thunderstorm. I say “experience” because that’s precisely what happens—they’re not just watching it approach, Grey transports you there and allows you to experience the moment with them: you can hear “the low, dull, and rumbling roll of thunder” in the distance, and “the faint murmur and moan and mourn of the wind singing in the caves,” you can feel the temperature fluctuations on your skin as the wind twirls and dances around you, and you can smell the life of fresh earth and summer rain in the air just before the storm unleashes its fury.

That’s the genius of Grey: he’s not just telling you a story—he’s providing you with such an accumulation of vivid, immersive detail that you’re actually there experiencing the story with the characters as it slowly unravels and reveals itself.

Which brings me to another point: Riders of the Purple Sage is generally regarded as the story singularly responsible for shaping the overarching formula of the western genre, so I assumed that after being exposed to over a century’s worth of western stories since this book’s original publication in 1912, all whose lineage can invariably be traced to this story, then naturally I would encounter enough now-clichés as to reveal major plot points and their conclusion long before they actually arrived. However, that’s not the case at all. So swept up in the experience was I that I never saw any of the plot points coming, nor most especially the conclusion. A fact that I find astounding given the story’s age and its revered place within the genre.

Looking at the novel now, and knowing the story within, it’s no wonder this book is Grey’s most popular and best-selling. If I had to describe it in one word it would be masterful.

The only real wonder is why I didn’t read it sooner, even given my L’Amour bias—which is to say that if you, dear reader, possess a western bias that has kept you from reading Zane Grey, then this is the book for you.

Before reading this book, I thought of Zane Grey as: Louis L’Amour, but wordier.

And now—at the risk of being tarred and feathered by the L’Amour die-hards—I think of Zane Grey as: Louis L’Amour, but better.

Sorry, dad!

Circling back to movies, I enjoyed this story so much that I decided to seek out all of its movie adaptations because I wanted to see how varying filmmakers tackled this story and how their approach to it evolved over the course of a century.

It has been adapted for the screen five times, with the years of release being 1918, 1925, 1931, 1941, and 1996.

The 1918 version was likely lost in the 1937 20th Century-Fox vault fire, whose details I wasn’t fully aware of until researching why the 1918 version isn’t available anywhere: more than 75 percent of Fox’s feature films from before 1930 were lost in the fire.

However, Fox’s 1925 adaptation starring Tom Mix and Mabel Ballin survived, and while it is a silent film and only an hour long, it is a fairly faithful adaptation. Tom Mix’s Lassiter being possibly the most reverent to the story’s original.

Next comes the 1931 and 1941 versions. Of the two, each with sound and also an hour long, the 1931 version starring George O’Brien and Marguerite Churchill is the far better of the two. However, this adaptation takes some inexplicable liberties with the story, which the 1941 version retains, making it more of a remake of the 1931 version rather than its own adaptation of the novel. The 1941 version even recycles and remixes some of the shots from the 1931 version.

All three of these adaptations, perhaps unsurprisingly, eschew any mention of Mormons or Mormonism.

Lastly, there is the 98-minute 1996 version starring Ed Harris and Amy Madigan. Of the four adaptations currently available, this version is the most faithful to the original story. In it, we get all of the primary and supporting characters and their individual storylines (however brief), and this version embraces the Mormon aspects of the story and walks that fine line between the religion’s faith and pretensions nearly as well as Grey did himself. Being an adaptation, it strays from the novel in different ways, the most head-scratching invention being Ed Harris’ hair, but overall it’s a solid western. Certainly worth the watch if you’re a western fan, or a (soon-to-be) fan of this book.

Now, as for the story’s text, wordy though Grey was, he still wrote for the masses, so we were not entirely surprised at how little editing Heathening was required on our part.

As per our usual, we’ve swapped out some hyphened words for their modern equivalents: to-day is now today, camp-fire has become campfire, and so on.

Additionally, we’ve added over 40 footnotes, most of which are explanations of certain horse-riding terms, or definitions of archaic or literary words that Grey conservatively peppers throughout the text.

As a preface of sorts, we have included Grey’s essay that he contributed to the 1921 book My Maiden Effort, wherein Grey tells of his first two literary efforts: the first, a short story he wrote as a “young ruffian”; the second, his first novel that he ultimately self-published when no other publisher would. We include it because it gave us more respect for Grey—in it, you see all of the grit and dogged determination in micro that makes the macro of Riders of the Purple Sage so great.

Finally, in 1915 Grey published a sequel to this story, The Rainbow Trail, and you can bet your sweet bippy that we’re already hard at work on it—which is to say: more Zane Grey Heathen Editions coming soon-ish!

God speed you.

Sheridan Cleland

Co-Heathen

The Heathen Newsletter

Want to be kept in the loop about new Heathen Editions, receive discounts and random cat photos, and unwillingly partake in other tomfoolery? Subscribe to our newsletter! We promise we won’t harass you – much. Also, we require your first name so that we can personalize your emails. ❤️

@heatheneditions #heathenedition

Copyright © 2026 Heathen Creative, LLC. All rights reserved.