No products in the cart.

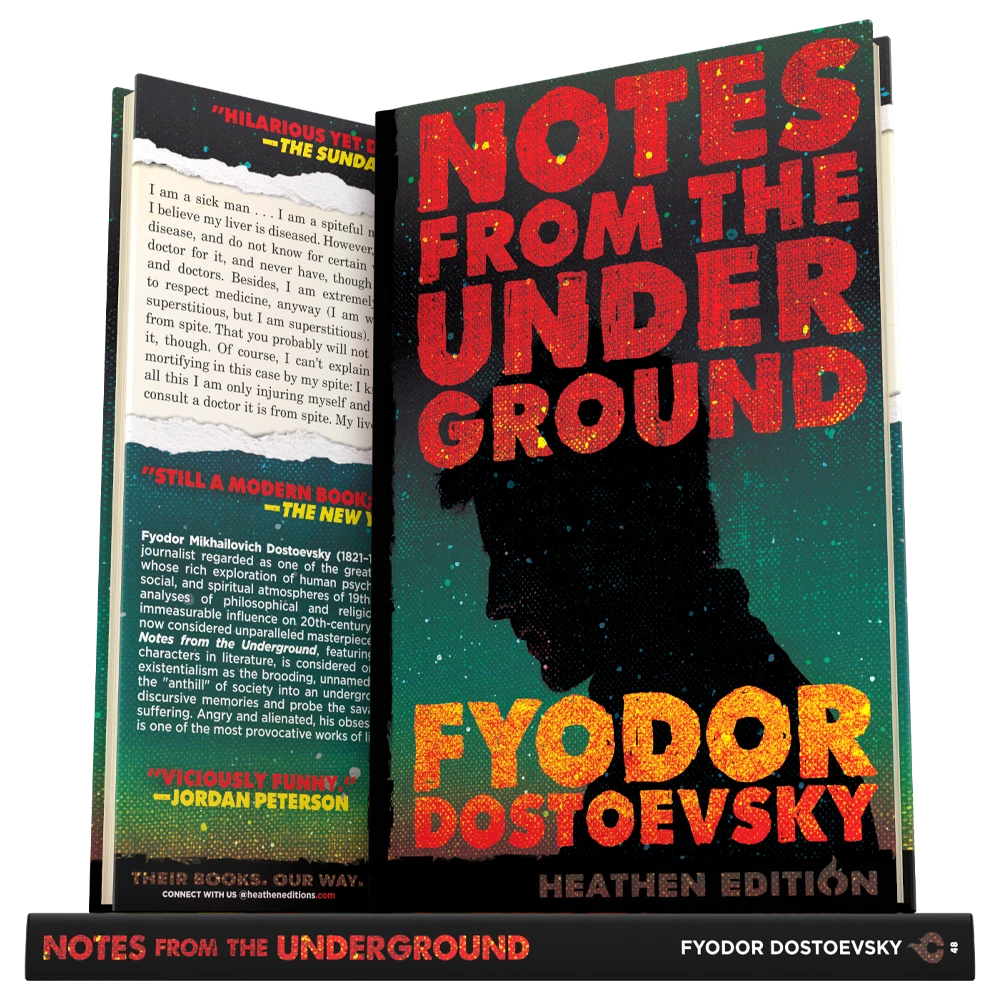

Notes from the Underground

Spine #48

Author

Fyodor Dostoevsky

Translator

Constance Garnett

First Edition

1864

Heathen Edition

February 10, 2024

Refreshed

Pages

170

Heathen Genera

Existentialicious

Paperback ISBN

978-1-948316-48-4

Hardcover ISBN

978-1-963228-48-9

I am a sick man . . . I am a spiteful man. I am an unattractive man. I believe my liver is diseased. However, I know nothing at all about my disease, and do not know for certain what ails me. I don't consult a doctor for it, and never have, though I have a respect for medicine and doctors. Besides, I am extremely superstitious, sufficiently so to respect medicine, anyway (I am well-educated enough not to be superstitious, but I am superstitious). No, I refuse to consult a doctor from spite. That you probably will not understand. Well, I understand it, though. Of course, I can't explain who it is precisely that I am mortifying in this case by my spite: I know better than anyone that by all this I am only injuring myself and no one else. But still, if I don't consult a doctor it is from spite. My liver is bad, well—let it get worse!

Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky (1821–1881) was a Russian author and journalist regarded as one of the greatest novelists in all of literature whose rich exploration of human psychology in the troubled political, social, and spiritual atmospheres of 19th-century Russia and penetrating analyses of philosophical and religious themes at large had an immeasurable influence on 20th-century fiction, with many of his works now considered unparalleled masterpieces. His revolutionary 1864 novella Notes from the Underground, featuring one of the most remarkable characters in literature, is considered one of the first works of literary existentialism whose brooding, unnamed narrator defiantly retreats from the “anthill” of society into an underground existence to document his discursive memories and probe the savage truth of the torment he is suffering. Angry and alienated, his obsessive, self-contradictory narrative is one of the most provocative works of literature ever written.

Test Your Might

Paperback

OTHER RETAILERS

Rate & Shelve It

Hardcover

OTHER RETAILERS

Rate & Shelve It

"Still a modern book; it still can kick."

The New Yorker

Heathenry

Contents

Praise

Details

Heathenry

Our greatest pleasure in readying this book for its Heathen tenure was rediscovering and connecting its many refractions throughout popular culture.

Palahniuk’s Fight Club knuckles to mind.

Ditto Scorsese’s Taxi Driver.

Also, Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye.

Deeper, Conrad’s The Heart of Darkness.

We recently published a Kafka collection, and yep.

Speaking of WE—by fellow Russian Yevgeny Zamyatin—we’re publishing that, too, and most definitely.

A Clockwork Orange.

American Psycho.

1984.

In all, backlit by smoldering fires of self-loathing, the long shadow of the Underground Man sways and sashays, like Morrissey teasing another encore.

Just look for him, he’s there, assuredly, in any tale of mopey man, especially if unreliable narrator.

Stop me, oh-oho, stop me . . .

And, to beat all, the Underground Man’s lit powder keg of vicious thought suddenly manifesting as self-contradictory, puff-and-smoke awkwardness is always spit-take funny.

It melds bits of Nicolas Winding Refn, High Fidelity, Charlie Kaufman, Scott Pilgrim, Wes Anderson, Rick and Morty.

In fact, that’s how we envisioned this bipolar tale as it unfurled on our mind-screen: a filmmaking team-up crossover event: the whimsical life of the Underground Man as directed by Wes Anderson interspersed with violent scattershots of his mind as birthed by Nicolas Winding Refn.

A chaotic and colorful center-framed charade!

That’s it, that’s all we’ve got, and with what little we’ve said we’ve probably said too much . . . moving on—

For our edition of this Dostoevsky masterpiece we’ve utilized the English translation by Constance Garnett as first published in her 1918 collection White Nights and Other Stories.

However, we’ve dropped Garnett’s British spellings in favor of their American alternates, so colour is now color, honour is now honor, and so on. And we’ve modernized some hyphened words, so good-bye is now goodbye, and so on.

Additionally, we’ve supplied the text with nearly 140 footnotes for clarity, context, sources, and translations as needed.

And, you know, there is one thing on which we can absolutely agree with the Underground Man:

“I might foam at the mouth, but . . . give me a cup of tea with sugar in it, and maybe I should be appeased.”

Cheers!

Contents

Heathenry: Thoughts on the Text

Notes from the Underground

Notes from the Underground

Praise

“Notes from the Underground is still a modern book; it still can kick.” —The New Yorker

“Hilarious yet disturbing.” —The Sunday Times

“Dostoevsky published Notes from the Underground in 1864, establishing his reputation as the most innovative and challenging writer of fiction in his generation in Russia.” —Rowan Williams, The Guardian

“Dostoyevsky’s Underground Man . . . is perhaps the greatest reliably unreliable narrator in world fiction.” —The New York Times

“It’s a brilliant book, it’s viciously funny, and it’s so psychologically alive . . . it’s one of the most remarkable criticisms of utopianism I’ve ever read . . . If you’re interested in psychology, Dostoevsky is the person for you.” —Jordan Peterson

“The most unflinching study of self-loathing in the literary canon.” —The Irish Times

“Notes from the Underground, with its mood of intellectual irony and alienation, can be seen as the first modern novel . . . That sense of the meaningless of existence that runs through much of the twentieth-century writing — from Conrad and Kafka, to Beckett and beyond — starts in Dostoevsky’s work.” —Malcolm Bradbury

“Dostoevsky, the only psychologist from whom I had something to learn.” —Friedrich Nietzsche, Twilight of the Idols

“[Dostoevsky] was a psychologist before psychology existed, and his observations were acute and universal.” —DBC Pierre

Details

Notes from the Underground

Heathen Edition #48Published: February 10, 2024

Format: Paperback

Interior: Black & White on Cream Paper

Pages: 170 (+2 POD)

Language: English

Annotations: 138 Footnotes

Illustrations: 6

The Heathen Newsletter

Want to be kept in the loop about new Heathen Editions, receive discounts and random cat photos, and unwillingly partake in other tomfoolery? Subscribe to our newsletter! We promise we won’t harass you – much. Also, we require your first name so that we can personalize your emails. ❤️

@heatheneditions #heathenedition

Copyright © 2026 Heathen Creative, LLC. All rights reserved.