No products in the cart.

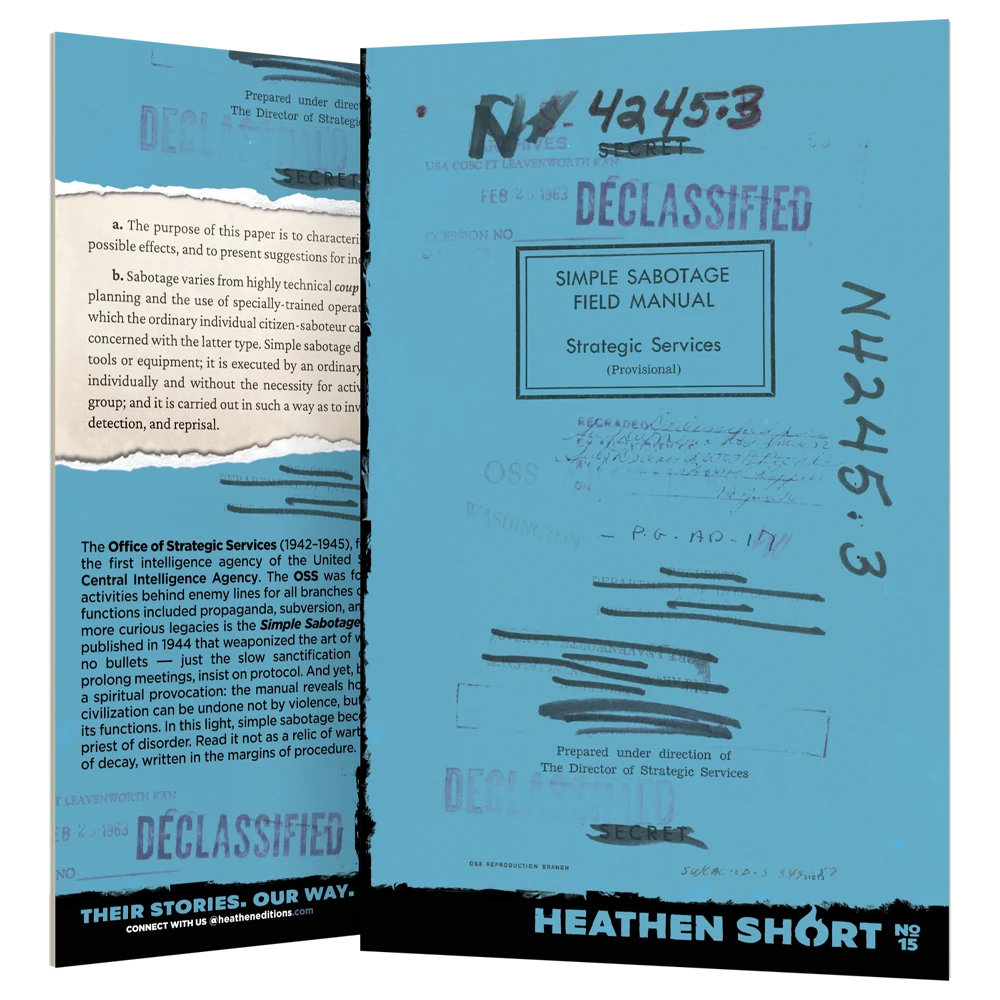

Simple Sabotage Field Manual

Heathen Short #15

Author

Office of Strategic Services

Translator

First Edition

January 17, 1944

Heathen Short

January 17, 2026

Refreshed

Pages

48

Heathen Genera

Rebellion 101

ISBN

979-8-90075-015-6

a. The purpose of this paper is to characterize simple sabotage, to outline its possible effects, and to present suggestions for inciting and executing it.

b. Sabotage varies from highly technical coup de main acts that require detailed planning and the use of specially-trained operatives, to innumerable simple acts which the ordinary individual citizen-saboteur can perform. This paper is primarily concerned with the latter type. Simple sabotage does not require specially prepared tools or equipment; it is executed by an ordinary citizen who may or may not act individually and without the necessity for active connection with an organized group; and it is carried out in such a way as to involve a minimum danger of injury, detection, and reprisal.

The Office of Strategic Services (1942–1945), formed during World War II, was the first intelligence agency of the United States and predecessor to the Central Intelligence Agency. The OSS was created to coordinate espionage activities behind enemy lines for all branches of the U.S. Armed Forces; other functions included propaganda, subversion, and psychological operations. Among its more curious legacies is the Simple Sabotage Field Manual, a slim document published in 1944 that weaponized the art of workaday disruption. No bombs, no bullets — just the slow evisceration of efficiency: misfile papers, prolong meetings, insist on protocol. And yet, beneath its tactical clarity pulses a stark insight into how fragile order truly is — how civilization can be undone not by violence, but through the gradual erosion of its functions. In this light, simple sabotage becomes a methodical practice, and the saboteur an agent of organizational unraveling. Read it not as a relic of wartime cunning, but as a diagnosis of systemic vulnerability, written in the margins of procedure.

Test Your Might

In stock

OTHER RETAILERS

Rate & Shelve It

The contents of this Manual should be carefully controlled and should not be allowed to come into unauthorized hands.

Heathenry

Contents

Praise

Details

Heathenry

Today, the Simple Sabotage Field Manual stands as a concise record of how the OSS understood organizational vulnerability and the strategic value of disruption. It demonstrates that effective sabotage does not always require Hollywood-style explosions or highly-specialized and expertly-trained operatives; it can be carried out through small, successive acts that degrade efficiency, slow decision‑making, and strain administrative systems.

Read in this context, the manual is not a curiosity but a clear articulation of how the OSS sought to weaken enemy capacity through methods accessible to anyone willing to participate. Its lessons remain a study in how complex organizations fail — and how they can be made to fail through targeted, systemic obstruction and incremental impairment.

And yet, the Simple Sabotage Field Manual is not buried in the archives of military history, collecting dust on some long forgotten shelf. After the war, its guidance circulated in unofficial translations produced by resistance groups, appeared in Cold War counter‑administrative doctrine, and resurfaced decades later when business analysts shockingly noted its uncanny resemblance to modern workplace dysfunction.

Which raises an unavoidable question: how much of this manual do you recognize in your own professional life? When you sit through a meeting that drifts without purpose, when a simple task becomes mired in procedural delay, when communication chains grow needlessly complex, or when decisions stall under the weight of bureaucratic oversight — are you witnessing ordinary inefficiency, or echoes of a sabotage stratagem once taught to civilians resisting an enemy occupation?

The Simple Sabotage Field Manual may have been a product of wartime necessity, but its techniques have slipped into everyday organizational behavior, surfacing in offices, institutions, and corporate cultures the world over, and most of them have never even heard of the OSS (and would probably assume you’re speaking of some computer operating system at the mere mention of its acronym). The relevance of the Simple Sabotage Field Manual endures not because we are surrounded by saboteurs, but because the vulnerabilities it identified remain embedded in the systems we inhabit, in the processes we engage daily.

Which leaves one final consideration: in systems built on routines, procedures, and interlocking responsibilities, where do you stand? When you postpone a decision because [insert arbitrary requirement here], when you forward an email instead of answering it, when you follow a rule to the letter knowing it will delay everything — are these moments of ordinary workplace friction, or are they forms of Simple Sabotage by another name?

The real question, then, is not whether sabotage exists in your workplace, but whether you have ever participated in it, knowingly or not.

Finally, a quick note on the text itself: our only additions consist of the thirty-odd footnotes we’ve appended throughout the manual for clarity, context, and commentary where necessary.

With that: end of briefing, proceed as directed—

Contents

Heathenry: A Briefing on the Manual

1. Introduction

2. Possible Effects

3. Motivating the Saboteur

4. Tools, Targets, and Timing

5. Specific Suggestions for Simple Sabotage

1. Introduction

2. Possible Effects

3. Motivating the Saboteur

4. Tools, Targets, and Timing

5. Specific Suggestions for Simple Sabotage

Praise

Details

Simple Sabotage Field Manual

Heathen Short #15Published: January 17, 2026

Format: Paperback

Retail: $6.95

ISBN-13: 9798900750156

Dimensions: 8.5 x 5.5 x 0.125 inches

Weight: 2.8 oz

Cover: Matte Finish

Interior: Black & White on Cream Paper

Pages: 48 (+2 POD)

Language: English

Annotations: 33 Footnotes

Illustrations: 4

- Title Page

- Heathenry Flame

- Honorary Heathen Headshot: Office of Strategic Services

- End Title

- History / Wars & Conflicts / World War II

- History / Military / Intelligence & Espionage

- Political Science / Propaganda

The Heathen Newsletter

Want to be kept in the loop about new Heathen Editions, receive discounts and random cat photos, and unwillingly partake in other tomfoolery? Subscribe to our newsletter! We promise we won’t harass you – much. Also, we require your first name so that we can personalize your emails. ❤️

@heatheneditions #heathenedition

Copyright © 2026 Heathen Creative, LLC. All rights reserved.