No products in the cart.

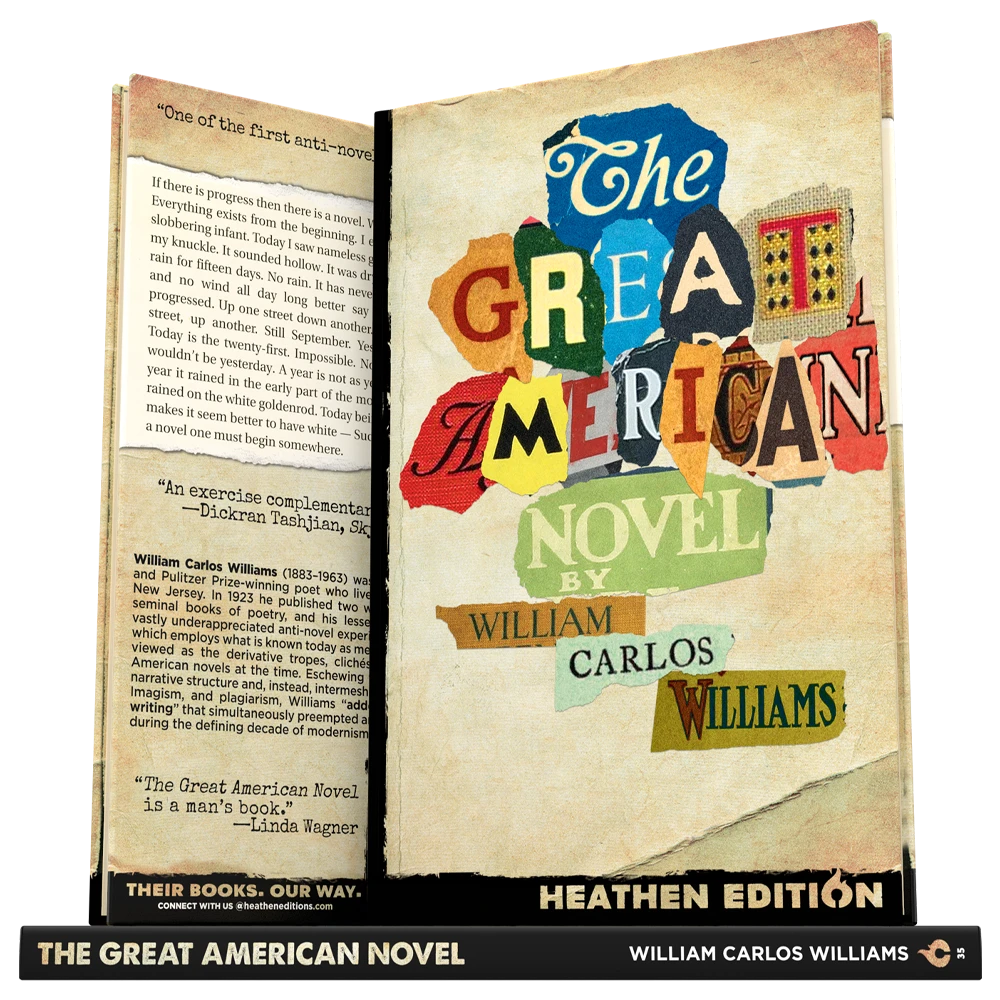

The Great American Novel

Spine #35

Author

William Carlos Williams

Translator

First Edition

1923

Heathen Edition

August 14, 2023

Refreshed

Pages

118

Heathen Genera

Satireality

Paperback ISBN

978-1-948316-35-4

Hardcover ISBN

978-1-963228-35-9

If there is progress then there is a novel. Without progress there is nothing. Everything exists from the beginning. I existed in the beginning. I was a slobbering infant. Today I saw nameless grasses — I tapped the earth with my knuckle. It sounded hollow. It was dry as rubber. Eons of drought. No rain for fifteen days. No rain. It has never rained. It will never rain. Heat and no wind all day long better say hot September. The year has progressed. Up one street down another. It is still September. Down one street, up another. Still September. Yesterday was the twenty-second. Today is the twenty-first. Impossible. Not if it was last year. But then it wouldn’t be yesterday. A year is not as yesterday in his eyes. Besides last year it rained in the early part of the month. That makes a difference. It rained on the white goldenrod. Today being misplaced as against last year makes it seem better to have white — Such is progress. Yet if there is to be a novel one must begin somewhere.

William Carlos Williams (1883–1963) was an American physician, author, and Pulitzer Prize-winning poet who lived most of his life in Rutherford, New Jersey. In 1923 he published two works: Spring and All, one of his seminal books of poetry, and his lesser-known, much-overlooked, and vastly underappreciated anti-novel experiment The Great American Novel, which employs what is known today as metafiction to satirize what Williams viewed as the derivative tropes, clichés, and formulaic unoriginality of American novels at the time. Eschewing the time and space of traditional narrative structure and, instead, intermeshing elements of Dadaism, Cubism, Imagism, and plagiarism, Williams “added a new chapter to the art of writing” that simultaneously preempted and foreshadowed postmodernism during the defining decade of modernism.

Test Your Might

Paperback

OTHER RETAILERS

Rate & Shelve It

Hardcover

OTHER RETAILERS

Rate & Shelve It

"One of the first anti-novels written in the U.S."

Webster Schott

Heathenry

Contents

Praise

Details

Heathenry

If you have never read The Great American Novel by William Carlos Williams, then I suggest one of two options:

A. Skip this intro and dive in cold. Nuevo Mundo!

B. Read this intro so as to better prepare for the coming assault.

Assault because that’s what this book does to my brain: assaults it violently with inspiration, the way Williams bobs and weaves through the composite narrative, rocketing back and forth through space and time willy-nilly, shuffling through a litany of -isms with chaotic precision — Dadaism, literary cubism, imagism, plagiarism — all while embracing modernism, but employing metafiction and postmodernism, both before they were words —— and all with an eye set squarely on metamodernism.

All this 100 years ago, just one year after James Joyce published his genre-defining modernist masterpiece Ulysses, and all from a guy who was a physician first.

This tiny book is a lot.

Every time I read this book it spurs me to write, a rocket fuel fill-up for my creative engine bludgeoned into inspired compulsion.

I don’t want to spoil anything more, but there are three quotes I wish I would have chanced upon before reading this book the first time:

“The Great American Novel is in no sense a finished work; it keeps turning back on itself and beginning all over again.”1Breslin, James E.B. (1970). The Fiction of a Doctor. William Carlos Williams: An American Artist (pp. 126-127). Oxford University Press.

“. . . an entire book written incidentally while the author searches for an opening sentence.”2Burke, K. (1927, December). William Carlos Williams, The Methods Of. The Dial, 82, (p. 98).

“Williams’s title is ironic, for The Great American Novel is not a novel at all but an improvisatory reflection upon the impossibility of writing the Great American novel.”3Witemeyer, Hugh. (1997). “Plagiarism in ‘The Great American Novel’: The Ethics of Collage.” William Carlos Williams Review, 23(1), pp. 1–13.

In short, The Great American Novel by William Carlos Williams is the story of a man obsessed with beginnings writing a story of his attempt to repeatedly begin a story.

If that sentence alone does not inspire you, then I suggest one of two options:

A. Continue to the next page.

B. Read on!

Sheridan Cleland

Co-Heathen

P.S. I nearly forgot to mention that we’ve updated some hyphened words to their modern equivalents (good-bye is now goodbye, mid-day has become midday, and so on) and we’ve appended over 230 footnotes to identify and clarify the staggering number of references and sources utilized by Williams throughout the text. Enjoy!

Contents

Heathenry: Thoughts on the Text

The Great American Novel

The Great American Novel

Praise

“The Great American Novel sprawls in all directions with a protean elusiveness . . . an exercise complementary to European Dada . . . he cleared out the past by turning from Europe to American in order to create a new art, unrecognized as such by the standing cultural order.” —Dickran Tashjian, Skyscraper Primitives

“One tendency, evident in the novel from André Gide to John Barth, has been to make self-conscious struggle with literary form into the fictional subject itself. Williams appears to have been one of the first twentieth-century writers to try this . . . Considered in its own right, The Great American Novel has a speed, intensity, and exuberance that carry it along in spite of its obscurities.” —James E. Breslin, William Carlos Williams: An American Artist

“No jokes or puns, no neologisms, no portmanteau words — Williams’ novel asks nothing from the reader except the seriousness of mind to shape the fragmented parts into a whole . . . The Great American Novel is a man’s book.” —Linda Wagner, The Prose of William Carlos Williams

“Williams’ ‘struggle’ to begin his ‘Great American Novel’ quickly becomes a metaphor for all ‘beginnings’ — all attempts by men to create anew and all attempts of new things to realize themselves.” —James Guimond, The Art of William Carlos Williams

“The Great American Novel was one of the first anti-novels written in the U.S. — plotless, hostile to the tradition of the novel, hung up on problems of language and time, indifferent to the attention span of its readers, capricious in selection of materials, hiding treasures of description and narration in fogs of aesthetic argument. It requires functional devotion to Williams to read the book once. Read twice it becomes a delight.” —Webster Schott

Details

The Great American Novel

Heathen Edition #35Format: Paperback

Interior: Black & White on Cream Paper

Pages: 118 (+2 POD)

Language: English

Annotations: 236 Footnotes

Illustrations: 4

The Heathen Newsletter

Want to be kept in the loop about new Heathen Editions, receive discounts and random cat photos, and unwillingly partake in other tomfoolery? Subscribe to our newsletter! We promise we won’t harass you – much. Also, we require your first name so that we can personalize your emails. ❤️

@heatheneditions #heathenedition

Copyright © 2026 Heathen Creative, LLC. All rights reserved.