No products in the cart.

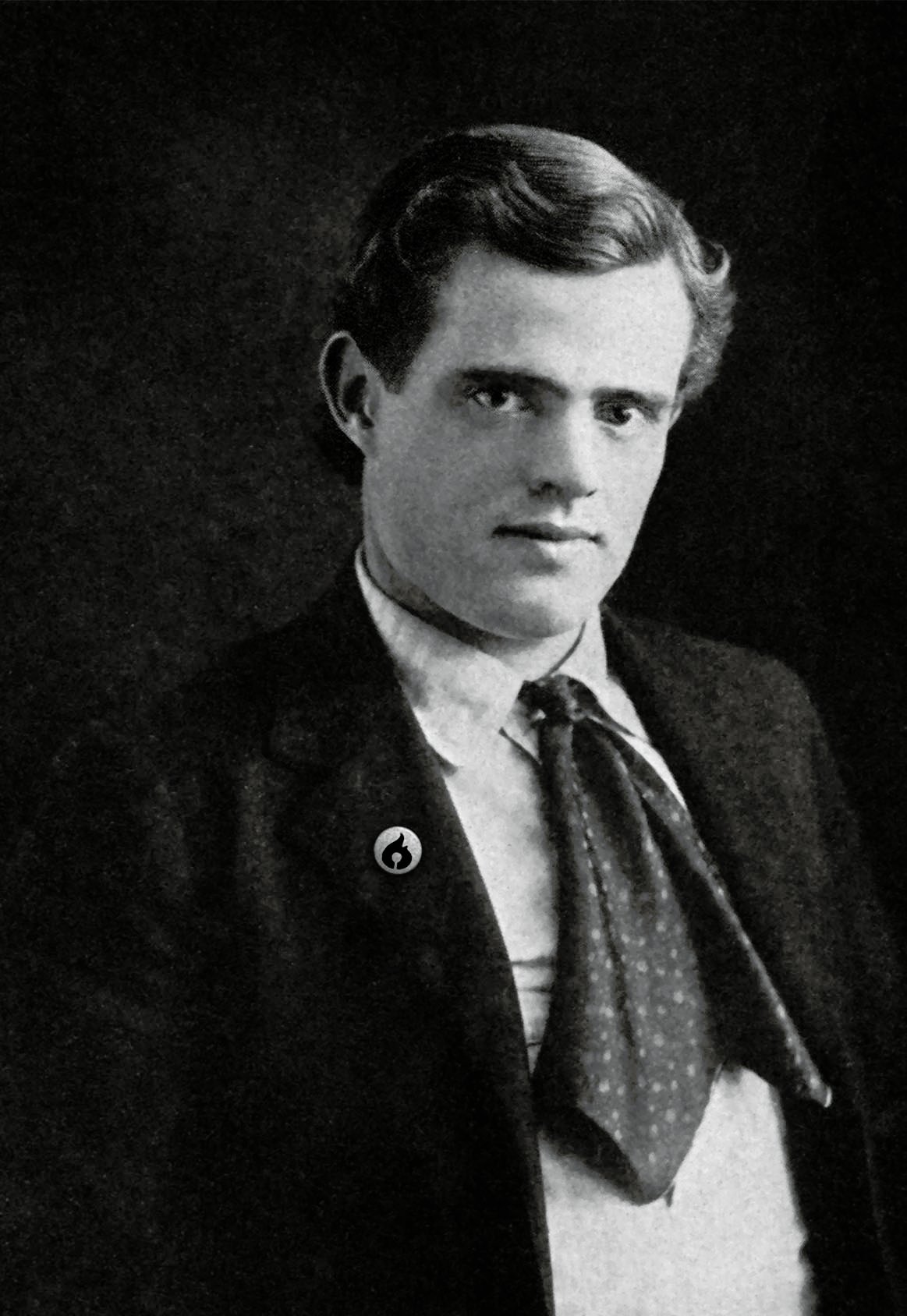

The following interview with Jack London was originally published in What I Think: A Symposium on Books and Other Things by Famous Writers of Today (1921) edited by Herbert Greenhough Smith.

How Jack London broke into print is a story which has been told before, but which is well worth the telling again. He himself said that ever since he was eight years old he had been on the hunt for his boyhood. Perhaps he never found it. At fifteen he was a man and had been a ranchman for seven years. True, he had had a few months of schooling at two schools, but never remembered ever learning anything at either.

When he went with his people on a Californian ranch, London found time to read Washington Irving’s Alhambra. He wasn’t nine then, and he was so fascinated with the book that he wanted to discuss it with the other “ranchmen.” But to his dismay they knew nothing about books, and their ignorance shocked him. The hired men lent him dime novels, and as his work was to watch the bees while sitting under a tree from sunrise till late in the afternoon—waiting for the swarming—he had plenty of time to read and dream. His favourite book was Ouida’s Signa and he read it over and over again, but never knew the end of the story until he was grown up, for the last chapters were missing.

Then Jack London left the ranch and went to Oakland, where he sold newspapers. He was eleven then, and from that age to sixteen he worked at anything that turned up. The number of occupations which at different times attracted Jack London must have run into many hundreds.

“Then,” he said, “the adventure-lust was strong within me, and I left home. I didn’t run, I just left—went out in the bay, and joined the oyster pirates. The days of the oyster pirates are now past, and if I had got my dues for piracy I would have been given five hundred years in prison. Oddly enough, my next occupation was on a fish patrol, where I was entrusted with the arrest of any violators of the fishing laws.

“But you want to know how I broke into print. Well, in my fitful days I had written the usual compositions which had been praised in the usual way, and when I got a job in a jute mill I still had an occasional try at writing. One day my mother came to me and said that a prize was being offered in the San Francisco Call for a descriptive article. She urged me to try for it; she knew that I should win it! And to please her I decided to make an attempt, taking as my subject, ‘Typhoon off the Coast of Japan.’ I was determined to write something with which I was fairly familiar. But I was working thirteen hours a day in the jute mill, and little time was left for composition. Very tired and sleepy, and knowing I had to be up at half-past five, I began the article at midnight and worked straight on until I had written two thousand words, the limit of the article, but with my ideas only half worked out. The next night, under the same conditions, I continued, adding another two thousand words before I finished, and then the third night I spent in cutting out the excess. The first prize came to me, and the second and third went to students of the Stanford and Berkeley Universities. This success seriously turned my thoughts to writing, but my blood was still too hot for a settled routine, so with the exception of a little gush which I sent to the Call, and which that journal promptly rejected, I deferred breaking farther into literature until my mind was more fully settled.

“In my nineteenth year I returned to Oakland and entered the High School there. Of course, they had the usual monthly or weekly magazine I forget which and I wrote stories for it, consisting mostly of accounts of my sea and tramping experiences. I stopped there for a year, doing janitor work as a means of livelihood, and then left and was my own schoolmaster for three months, cramming hard in order to enter the University of California. To support myself I took a job in a laundry, and while ironing shirts and singeing collars evolved some of the plots which stood me in good stead in future stories.

“Then I left California and went to the Klondyke to prospect for gold. At the end of a year I was obliged to come out owing to an outbreak of scurvy, and on the homeward journey of nineteen hundred miles in an open boat I made the only notes of the trip. It was in the Klondyke that I found myself. There nobody talks. Everybody thinks. You get your true perspective. I got mine. After returning to California I had a bad stroke of luck. Work was scarce and I had nothing to do. Consequently my thoughts turned again to writing, and I wrote a story called ‘Down the River,’ which was rejected. While I was waiting for this rejection I wrote a twenty- thousand-word serial for a news company. This was also rejected. But I wasn t discouraged. Just as soon as a manuscript was dispatched I would buckle to and write something else. I often wondered what an editor looked like. I had never seen one, and never at that time had come across anyone who had ever published anything. Then a Californian magazine accepted a short story and sent me five dollars. That was my second success in ‘breaking into print.’ And when I had received forty dollars for another short story I began to think that things were on the mend, and so they were.

“My first book—my real ‘break into print’ was published in 1900 under the title of The Son of the Wolf. It was something of a success, and I had many offers of newspaper work. But I had sufficient sense to refuse to be a slave to that man-killing machine, for such I hold a newspaper to a young man in his faming period. Not until I was well on my feet as a magazine writer did I do much work for newspapers. Then it did not matter, for I was not obliged to do more than I cared, and could quit when the spirit moved me to do so. But I do not forget that I first ‘broke into print’ through a newspaper, and for that reason I have a kindly feeling toward the Press. I suppose I should have ‘broken into print’ some time or another, but I always think it was my mother’s faith in me that turned my attention to literature as a profession.”

If you enjoyed this interview, check out Jack London’s book War of the Classes.

Jack London

- Writers on Writing

- 5 Minute Read

The Heathen Newsletter

Want to be kept in the loop about new Heathen Editions, receive discounts and random cat photos, and unwillingly partake in other tomfoolery? Subscribe to our newsletter! We promise we won’t harass you – much. Also, we require your first name so that we can personalize your emails. ❤️

@heatheneditions #heathenedition

Copyright © 2026 Heathen Creative, LLC. All rights reserved.