No products in the cart.

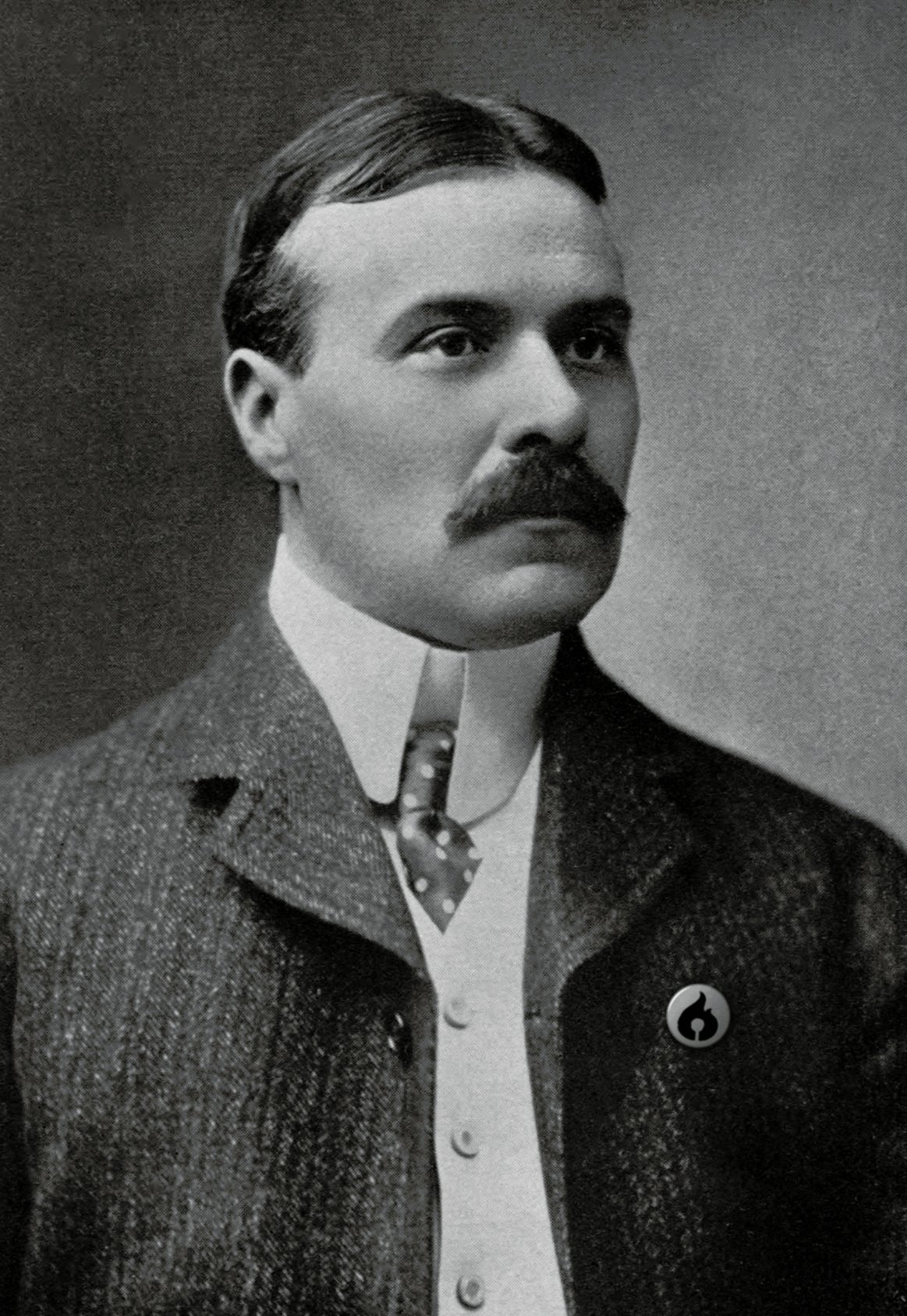

The following interview with Robert W. Chambers is excerpted from the book Fiction Writers on Fiction Writing (1923) edited by Arthur Sullivant Hoffman, wherein each participating author was asked the same twelve questions concerning their craft.

The second part was originally published in My Maiden Effort: Being the Personal Confessions of Well-Known American Authors as to Their Literary Beginnings (1921).

The second part was originally published in My Maiden Effort: Being the Personal Confessions of Well-Known American Authors as to Their Literary Beginnings (1921).

1. What is the genesis of a story with you—does it grow from an incident, a character, a trait of character, a situation, setting, a title, or what? That is, what do you mean by an idea for a story?

Robert W. Chambers (RWC): From an incident.

2. Do you map it out in advance, or do you start with, say, a character or situation, and let the story tell itself as you write? Do you write it in pieces to be joined together, or straightaway as a whole? Is the ending clearly in mind when you begin? To what extent do you revise?

RWC: Map it out in advance. Write it straightaway as a whole. Ending clearly in mind from the start. Revise murderously.

3. When you read a story to what extent does your imagination reproduce the story-world of the author—do you actually see in your imagination all the characters, action and setting just as if you were looking at an actual scene? Do you actually hear all sounds described, mentioned and inferred, just as if they were real sounds? Do you taste the flavors in a story, so really that your mouth literally waters to a pleasant one? How real does your imagination make the smells in a story you read? Does your imagination reproduce the sense of touch—of rough or smooth contact, hard or gentle impact or pressure, etc.? Does your imagination make you feel actual physical pain corresponding, though in a slighter degree, to pain presented in a story? Of course you get an intelligent idea from any such mention, but in which of the above cases does your imagination produce the same results on your senses as do the actual stimuli themselves?

If you can really “see things with your eyes shut,” what limitations? Are the pictures you see colored or more in black and white? Are details distinct or blurred?

If you studied geometry, did it give you more trouble than other mathematics?

Is your response limited to the exact degree to which the author describes and makes vivid, or will the mere concept set you to reproducing just as vividly?

Do you have stock pictures for, say, a village church or a cowboy, or does each case produce its individual vision?

Is there any difference in behavior of your imagination when you are reading stories and when writing them?

Have you ever considered these matters as “tools of your trade”? If so, to what extent and how do you use them?

RWC: It depends on the story. No limitations to “seeing.” Colors. Distinct. All mathematics annoy me. Response depends upon the author. No stock pictures. Do not resent many images if they are well done. Difference when reading and writing? Of course. As tools? Have given it no thought.

4. When you write do you center your mind on the story itself or do you constantly have your readers in mind? In revising?

RWC: The story only. In revising, the story alone.

5. Have you had a class-room or correspondence course on writing fiction? Books on it? To what extent did this help in the elementary stages? Beyond the elementary stages?

RWC: Rot!

6. How much of your craft have you learned from reading current authors? The classics?

RWC: Current authors, nothing. Classics, much.

7. What is your general feeling on the value of technique?

RWC: It is an essential part of all creative work.

8. What is most interesting and important to you in your writing—plot, structure, style, material, setting, character, color, etc.?

RWC: Fifty-fifty.

9. What are two or three of the most valuable suggestions you could give to a beginner? To a practised writer?

RWC: To a beginner, be sure you have something to say, then learn how to say it. To a practised writer, work and pray.

10. What is the elemental hold of fiction on the human mind?

RWC: Amusement.

11. Do you prefer writing in the first person or the third? Why?

RWC: It makes no difference.

12. Do you lose ideas because your imagination travels faster than your means of recording? Which affords least check—pencil, typewriter or stenographer?

RWC: Do not lose ideas thus. Pencil and eraser.

There was no romance connected with my maiden effort. The story was written in the evenings to mitigate the ennui of being obliged to live, for a while, in Germany.

During daylight hours I was busy painting. At night I preferred a pad, pencil, and my own company to any alternative which Bavaria had to offer.

So it happened that I perpetrated the paper-covered novelette called “In the Quarter.”

I had nothing particularly in view when I did it. Any excellence in it was due to my Mother’s criticisms of my own unwieldy and lumbering language.

When it was finished, my Father, who was departing for New York, took it with him. I don’t think that he thought much of it. His was that polished culture consequent upon intimate knowledge of all that is best in classic literature. My Mother was even more widely read in several modern languages, and I realize, now, that she tolerated the result of my efforts merely because she hoped it might lead to something better.

As I remember, now, all the good old conservative publishers declined to avail themselves of the opportunity to pitchfork me into the literary arena where critics raged and ravened. It remained for an obscure Chicago publisher to publish the story in paper and pay me, ultimately, $1501Adjusted for inflation (1894–2022), $150 is approximately $5,200 today. for selling a rather large edition and then several other editions.

Why anybody bought the book is beyond me. Eventually the publisher became bankrupt and I bought in the book and the plates, destroyed the latter, and have never re-issued the book.

I am sorry I cannot offer a more romantic and more interesting article for this series. But Truth is mighty and, sometimes, is told.

If you enjoyed this interview, check out Robert W. Chambers’ masterpiece The King in Yellow.

Robert W. Chambers

- Writers on Writing

- 5 Minute Read

The Heathen Newsletter

Want to be kept in the loop about new Heathen Editions, receive discounts and random cat photos, and unwillingly partake in other tomfoolery? Subscribe to our newsletter! We promise we won’t harass you – much. Also, we require your first name so that we can personalize your emails. ❤️

@heatheneditions #heathenedition

Copyright © 2026 Heathen Creative, LLC. All rights reserved.