No products in the cart.

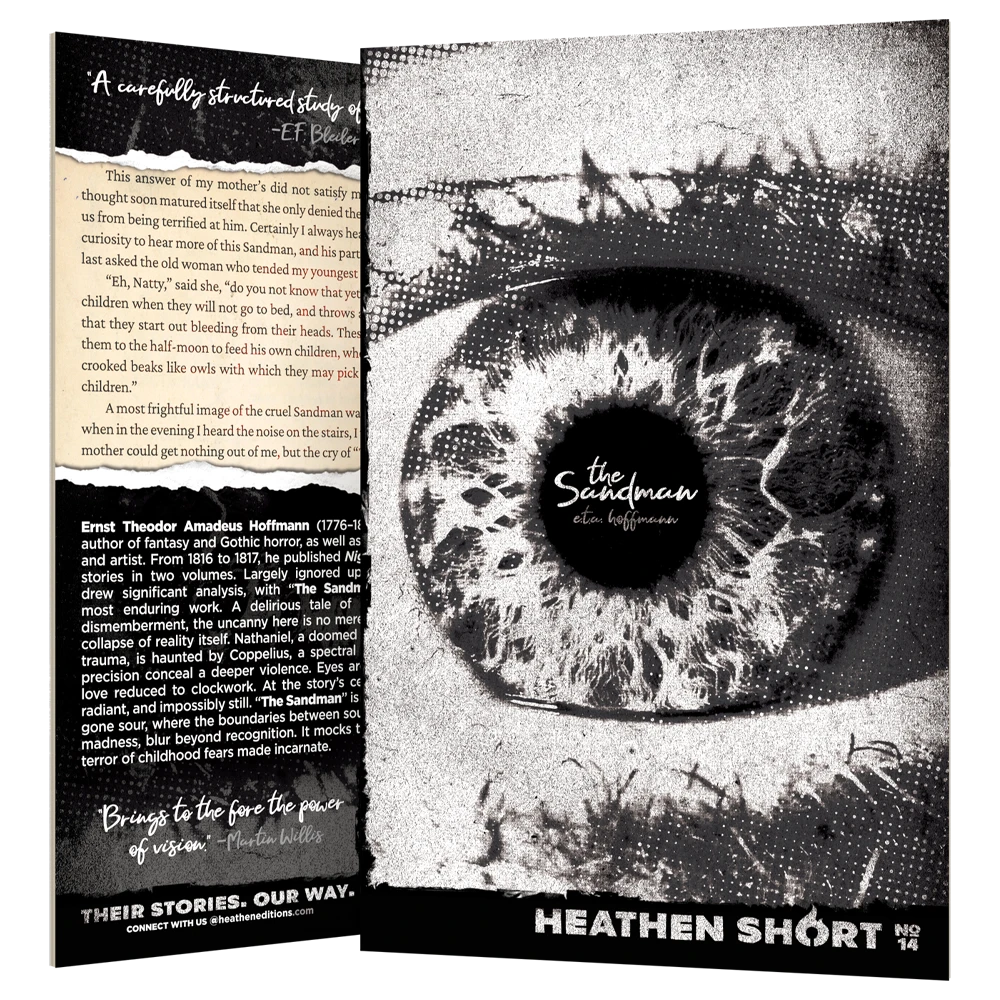

The Sandman

Heathen Short #14

Author

E.T.A. Hoffmann

Translator

John Oxenford

First Edition

1816 / 1844

Heathen Short

January 21, 2026

Refreshed

Pages

52

Heathen Genera

Existentialicious

ISBN

979-8-90075-014-9

This answer of my mother’s did not satisfy me — nay, in my childish mind the thought soon matured itself that she only denied the existence of the Sandman to hinder us from being terrified at him. Certainly I always heard him coming up the stairs. Full of curiosity to hear more of this Sandman, and his particular connection with children, I at last asked the old woman who tended my youngest sister what sort of man he was.

“Eh, Natty,” said she, “do you not know that yet? He is a wicked man, who comes to children when they will not go to bed, and throws a handful of sand into their eyes, so that they start out bleeding from their heads. These eyes he puts in a bag and carries them to the half-moon to feed his own children, who sit in the nest up yonder, and have crooked beaks like owls with which they may pick up the eyes of the naughty human children.”

A most frightful image of the cruel Sandman was horribly depicted in my mind, and when in the evening I heard the noise on the stairs, I trembled with agony and alarm. My mother could get nothing out of me, but the cry of “The Sandman, the Sandman!”

Ernst Theodor Amadeus Hoffmann (1776–1822) was a German Romantic author of fantasy and Gothic horror, as well as a jurist, composer, music critic, and artist. From 1816 to 1817, he published Night Pieces, a collection of eight stories in two volumes. Largely ignored upon release, several tales later drew significant analysis, with “The Sandman” emerging as Hoffmann’s most enduring work. A delirious tale of shattered vision and spiritual dismemberment, the uncanny here is no mere trick of perception — it is the collapse of reality itself. Nathaniel, a doomed romantic gripped by childhood trauma, is haunted by Coppelius, a spectral optician whose instruments of precision conceal a deeper violence. Eyes are plucked, souls distorted, and love reduced to clockwork. At the story’s center stands Olympia — silent, radiant, and impossibly still. “The Sandman” is a fever dream of Enlightenment gone sour, where the boundaries between soul and mechanism, memory and madness, blur beyond recognition. It mocks the rational mind and exalts the terror of childhood fears made incarnate.

Test Your Might

In stock

OTHER RETAILERS

Rate & Shelve It

"The Sandman" is a carefully structured study of developing insanity.

E.F. Bleiler

Supernatural Fiction Writers

Heathenry

Contents

Praise

Details

Heathenry

Now, for our Short, we have used the English translation by John Oxenford, first published in his 1844 collection Tales from the German, which included three Hoffmann stories. Oxenford’s own introduction to Hoffmann — and to “The Sandman” in particular — offers a revealing glimpse into how early English readers encountered him:

“No literature can produce a more original writer than Ernst Theodore Amadeus Hoffmann, from whom the translators have not scrupled to take three stories. Some have called Hoffmann an imitator of Jean Paul, but the assertion seems to be made rather because both writers are of an eccentric and irregular character than because their eccentricities and irregularities are similar. However wild may be the subjects of Hoffmann, and however rambling his method of treating them, his style is remarkably lucid; and while Jean Paul is one of the most difficult authors for a foreigner to read, Hoffmann is comparatively easy . . . Many of Hoffmann’s stories have been translated into English, but they have not been so successful [in England] as in France, where, when the translations appeared, they created a complete furore . . . In all these stories it will be observed that Hoffmann’s purpose is to point out the ill-effect of a morbid desire after an imaginary world, and a distaste for realities . . . Hoffmann seems to be exhibiting his own internal nature as the extreme of unhealthiness. The same tone may be perceived in his other writings, and his obvious reverence for the prosaic and commonplace, as the antithesis to himself, is remarkable. The story of “The Sandman” had its origin in a discussion which actually took place between La Motte Fouqué and some friends, at which Hoffmann was present. Some of the party found fault with the cold, mechanical deportment of a young lady of their acquaintance, while La Motte Fouqué zealously defended her. Here Hoffmann caught the notion of Olympia, and the arguments used by Nathaniel are those that were really employed by La Motte Fouqué.”

As for the text itself, we’ve updated some words which were once rendered as two but are now one (up stairs is now upstairs, any thing is now anything, and so forth), and we’ve jettisoned all of Oxenford’s British spellings in favor of their American counterparts (colour is now color, recognise is now recognize, and so on). However, the majority of our work has been concentrated on the 60+ footnotes we’ve appended throughout the text for context, clarity, and commentary where necessary.

Finally, what we Heathens love most about “The Sandman” is that it is a controlled collapse of certainty. Hoffmann dismantles the Enlightenment’s faith in perception and reason, revealing how easily the mind can be unseated when childhood terror is given adult form. The result is a narrative where soul and contrivance, memory and madness, refuse to stay in their proper places — this is a story that stares back at you with an icy, unblinking, unnerving, mechanical calm.

Contents

Heathenry: Thoughts on the Text

“The Sandman“

“The Sandman“

Praise

“E.T.A. Hoffmann’s fantastic burlesque and profound poetic power have conquered the world.” —The New York Times Book Review

“‘The Sandman’ is a carefully structured study of developing insanity that reveals Hoffmann’s deep interest in psychology.” —E.F. Bleiler, Supernatural Fiction Writers

“Hoffmann’s figures are, to him at least, absolutely real . . . In his stories he hovers always on the boundary between real and the supernatural, crossing and recrossing at will . . . one realm was as real to him as the other.” —Palmer Cobb, “Poe and Hoffmann”

“‘The Sandman’ is the prime object of analysis in Freud’s most important discussion of the fantastic, The Uncanny (1919).” —Eric S. Rabkin, Masterpieces of the Imaginative Mind

“Hoffmann was profoundly interested in the philosophers who were forebears of Jungian thought — Kant, Schelling, and G.H. von Schubert, to name the most important . . . Like Schelling and Schubert, Hoffmann believed that the unconscious was a person’s link to cosmic forces, if only her or she could understand its language.” —Joseph Andriano, Our Ladies of Darkness

“A story like ‘The Sandman’ is true, it gives literary shape to insights which cannot be conveyed in any way less grotesque, absurd, and uncanny.” —S.S. Prawer, Hoffmann’s Uncanny Guest

“E.T.A. Hoffmann, it will by now have been noticed, is by any standards a key figure in the development of the literary fantastic.” —Neil Cornwell, The Literary Fantastic

“‘The Sandman’ brings to the fore the power of vision . . . and deserve[s] to be better placed in the critical history of science fiction.” —Martin Willis, Mesmerists, Monsters, and Machines

“Hoffmann’s writing nearly always creates a sense of boundaries breaking down, of spiritual vertigo.” —Michael Dirda, Classics for Pleasure

Details

The Sandman

Heathen Short #14Published: January 21, 2026

Format: Paperback

Retail: $7.95

ISBN-13: 9798900750149

Dimensions: 8.5 x 5.5 x 0.125 inches

Weight: 2.8 oz

Cover: Matte Finish

Interior: Black & White on Cream Paper

Pages: 52 (+2 POD)

Language: English

Annotations: 61 Footnotes

Illustrations: 4

- Title Page

- Heathenry Flame

- Honorary Heathen Headshot: E.T.A. Hoffmann

- End Title

- Fiction / World Literature / Germany

- Fiction / Horror / Psychological

- Fiction / Gothic

The Heathen Newsletter

Want to be kept in the loop about new Heathen Editions, receive discounts and random cat photos, and unwillingly partake in other tomfoolery? Subscribe to our newsletter! We promise we won’t harass you – much. Also, we require your first name so that we can personalize your emails. ❤️

@heatheneditions #heathenedition

Copyright © 2026 Heathen Creative, LLC. All rights reserved.