No products in the cart.

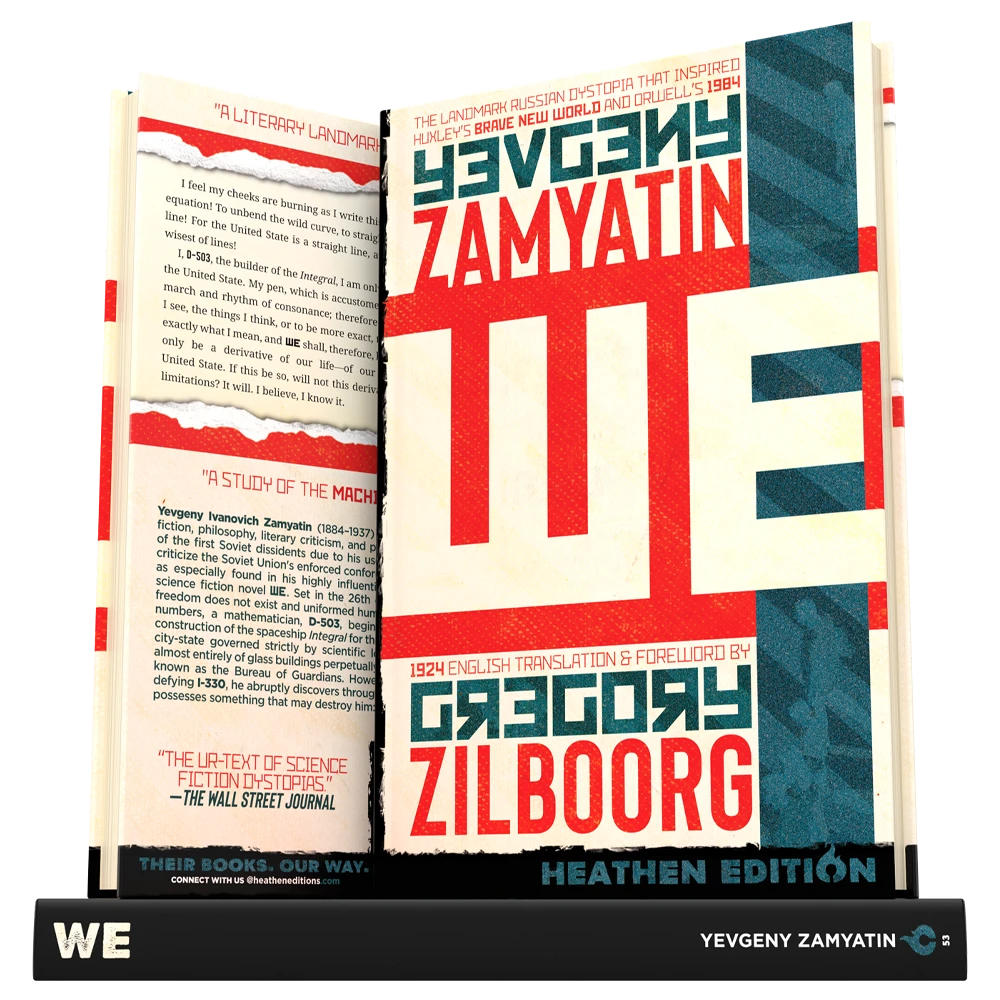

WE

Spine #53

Author

Yevgeny Zamyatin

Translator

Gregory Zilboorg

First Edition

1924

Heathen Edition

August 1, 2024

Refreshed

Pages

230

Heathen Genera

Rebellion 101

Paperback ISBN

978-1-948316-53-8

Hardcover ISBN

978-1-963228-53-3

I feel my cheeks are burning as I write this. To integrate the colossal, universal equation! To unbend the wild curve, to straighten it out to a tangent—to a straight line! For the United State is a straight line, a great, divine, precise, wise line, the wisest of lines!

I, D-503, the builder of the Integral, I am only one of the many mathematicians of the United State. My pen, which is accustomed to figures, is unable to express the march and rhythm of consonance; therefore I shall try to record only the things I see, the things I think, or to be more exact, the things we think. Yes, we; that is exactly what I mean, and WE shall, therefore, be the title of my records. But this will only be a derivative of our life—of our mathematical, perfect life in the United State. If this be so, will not this derivative be a poem in itself, despite my limitations? It will. I believe, I know it.

Yevgeny Ivanovich Zamyatin (1884–1937) was a Russian author of science fiction, philosophy, literary criticism, and political satire, now considered one of the first Soviet dissidents due to his use of literature to both satirize and criticize the Soviet Union’s enforced conformity and increasing totalitarianism, as especially found in his highly influential and widely imitated dystopian science fiction novel WE. Set in the 26th century, in a time when individual freedom does not exist and uniformed humans have no names, only assigned numbers, a mathematician, D-503, begins a journal while overseeing the construction of the spaceship Integral for the United State – a sprawling, urban city-state governed strictly by scientific logic and reason, and constructed almost entirely of glass buildings perpetually monitored by a secret police force known as the Bureau of Guardians. However, when D-503 meets the rule-defying I-330, he abruptly discovers through a blooming irrational love that he possesses something that may destroy him: an individual soul.

Test Your Might

Paperback

OTHER RETAILERS

Rate & Shelve It

Hardcover

OTHER RETAILERS

Rate & Shelve It

"A literary landmark, led the way to Brave New World and 1984."

Saturday Review

Heathenry

Contents

Praise

Details

Heathenry

. . . as for the text, we’ve used Gregory Zilboorg’s 1924 translation, which we’ve cross-referenced with nearly every other English translation currently in existence to ensure the accuracy of his work.

Also, a recurring overall criticism that I’ve noted by several readers and reviews of this novel is the confusion created by Zamyatin’s aforementioned use of alphanumerics for character names. Indeed, during my first reading of the book I found myself having trouble separating regular numbers from character numbers from hours and minutes from the protagonist speaking in first person, which is why our edition employs a unique formatting scheme that I haven’t observed in any other edition currently available and which I believe eliminates all confusion: any and all references to persons as Numbers will appear styled in an entirely different font, so rather than Numbers with a capital N, we designate them as NUMBERS, and instead of a character’s name, like our protagonist’s, D-503, appearing styled in the primary text font, his name will appear as D-503.

I believe this is especially helpful when Zamyatin shortens certain character names, like I-330 to I-, which is where the first person confusion really set in for me because, as a reader, I was asking is that I- as in me with a hyphen meaning I should pause, or is that I- as in the character I-330?—which required reading further for contextual clues, then rereading for clarification, before finally resuming the narrative . . . exhausting, to be sure.

How much simpler it is to read and process, in real time, I think, when her name appears styled differently as I- or I-330.

This small formatting detail is important, and it’s why we do what we do as Heathen Editions, because Zamyatin’s message and the wisdom he imparts via this cautionary tale is far too important for readers to be repeatedly hung up on wait, whosa-whatsa?

Also, in addition to the text’s seven original footnotes, we’ve added over 100 of our own to provide clarity, context, and commentary where necessary, as well as to identify certain sources quoted by Zamyatin, and to provide translations of foreign words or phrases.

Then, as an epilogue of sorts, we’ve included George Orwell’s review of WE, which first appeared in the Tribune for January 4, 1946. We’ve included it because we find it fascinating to read what one author of one of the oft-trio-ed crown jewels of satirical futuristic dystopian literature thinks of one of the others, especially when compared/contrasted with the third—straight from the horse’s mouth, as they say.

In all, I think these alterations make our edition the single best edition now currently available.

I am definitely biased, though . . .

Enjoy!

Sheridan Cleland

Co-Heathen

August 2024

Contents

Heathenry: Thoughts on the Text

Foreword by Gregory Zilboorg

WE

George Orwell’s Review

Foreword by Gregory Zilboorg

WE

George Orwell’s Review

Praise

“A literary landmark, led the way to Brave New World and 1984.” —Saturday Review

“Zamyatin’s influence on Orwell is beyond dispute.” —Alex M. Shane, The Life and Works of Evgenij Zamjatin

“. . . his book is not simply the expression of a grievance. It is in effect a study of the Machine, the genie that man has thoughtlessly let out of its bottle and cannot put back again. This is a book to look out for . . . ” —George Orwell

“One of the best!” —The New York Review of Books

“The ur-text of science fiction dystopias.” —Wall Street Journal

“The best single work of science fiction yet written.” —Ursula K. Le Guin

“Philosophical as Plato’s The Republic, interesting as the best utopias of H.G. Wells, cold as the muzzle of a loaded revolver, and sarcastic as Gulliver’s Travels, WE is a powerful challenge to all Socialist utopias.” —Pitirim A. Sorkin

“As the first major anti-utopian fantasy . . . has its own peculiar wryness and grace, sharper than the pamphleteering of 1984 or the philosophical schema of Brave New World, its celebrated descendants.” —Kirkus Reviews

“. . . along with Brave New World and 1984, forms a trio of world-famous works.” —SF and Fantasy Book Review

“FANTASTIC . . . In spite of its grim ending, almost lyrically optimistic!” —The New York Times

“1984 shares so many features with WE that there can be no doubt about its general debt to it . . . Orwell’s novel is both bleaker and more topical than Zamyatin’s, lacking entirely that ironic humour that pervades the Russian work.” —Robert Russell, Zamyatin’s We

Details

WE

Heathen Edition #53Published: August 1, 2024

Format: Paperback

Interior: Black & White on Cream Paper

Pages: 230 (+2 POD)

Language: English

Annotations: 129 New, 7 Original Footnotes

Illustrations: 4

The Heathen Newsletter

Want to be kept in the loop about new Heathen Editions, receive discounts and random cat photos, and unwillingly partake in other tomfoolery? Subscribe to our newsletter! We promise we won’t harass you – much. Also, we require your first name so that we can personalize your emails. ❤️

@heatheneditions #heathenedition

Copyright © 2026 Heathen Creative, LLC. All rights reserved.