No products in the cart.

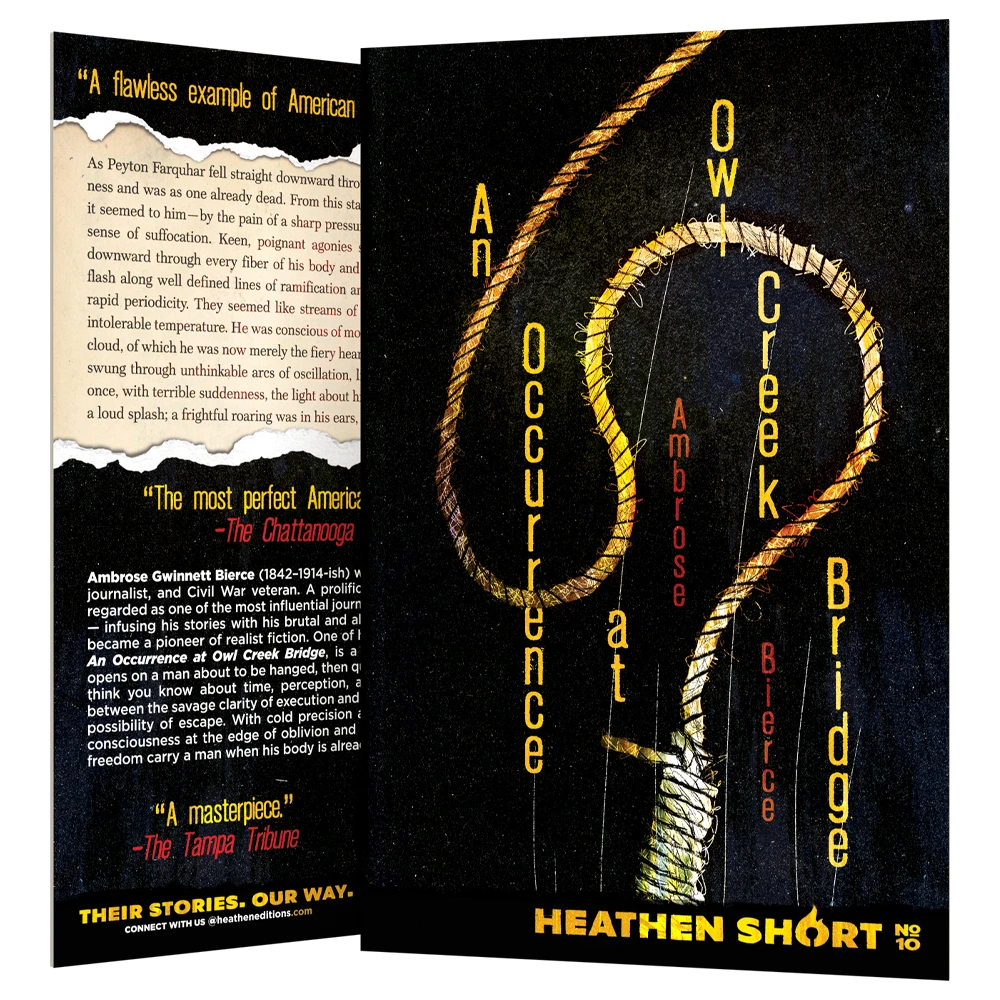

An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge

Heathen Short #10

Author

Ambrose Bierce

Translator

First Edition

July 13, 1890

Heathen Short

January 14, 2026

Refreshed

Pages

28

Heathen Genera

Existentialicious

ISBN

979-8-90075-010-1

As Peyton Farquhar fell straight downward through the bridge he lost consciousness and was as one already dead. From this state he was awakened—ages later, it seemed to him—by the pain of a sharp pressure upon his throat, followed by a sense of suffocation. Keen, poignant agonies seemed to shoot from his neck downward through every fiber of his body and limbs. These pains appeared to flash along well defined lines of ramification and to beat with an inconceivably rapid periodicity. They seemed like streams of pulsating fire heating him to an intolerable temperature. He was conscious of motion. Encompassed in a luminous cloud, of which he was now merely the fiery heart, without material substance, he swung through unthinkable arcs of oscillation, like a vast pendulum. Then all at once, with terrible suddenness, the light about him shot upward with the noise of a loud splash; a frightful roaring was in his ears, and all was cold and dark.

Ambrose Gwinnett Bierce (1842–1914-ish) was an American author, poet, journalist, and Civil War veteran. A prolific and versatile writer, he was regarded as one of the most influential journalists in the United States and — infusing his stories with his brutal and absurd wartime experiences — became a pioneer of realist fiction. One of his most famous short stories, “An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge,” is a deceptively simple tale that opens on a man about to be hanged, then quietly unravels everything you think you know about time, perception, and reality as the story slips between the savage clarity of execution and the strange, almost dreamlike possibility of escape. With cold precision and dark wit, Bierce explores consciousness at the edge of oblivion and asks how far can thoughts of freedom carry a man when his body is already falling?

Test Your Might

In stock

OTHER RETAILERS

Rate & Shelve It

"It is a flawless example of American genius."

Kurt Vonnegut

Heathenry

Contents

Praise

Details

Heathenry

Recently, while we Heathens were poring through Stephen Crane biographies for our work on “The Open Boat,” — itself a razor‑sharp piece of realist fiction and well worth your time! — we stumbled onto Crane’s thoughts about Ambrose Bierce and “An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge”. . .

“Nothing better exists,” Crane said. “That story contains everything.”

Crane then asked, “Has [Bierce] plenty of enemies?”

“More than he needs,” came the reply.

“Good. Then he will become an immortal.”

In late 1913, age 71, Bierce journeyed to Mexico, then in the throes of the Mexican Revolution, where, in Ciudad Juárez, he joined Pancho Villa’s army as an observer and witnessed the Battle of Tierra Blanca. Reports say Bierce then accompanied Villa’s army as far as the city of Chihuahua, and from there sent his final known letter, dated December 26, 1913, which concluded with, “As to me, I leave here tomorrow for an unknown destination.”

Then he vanished without a trace.

Whatever that destination, it made good Crane’s prophecy: Bierce stepped over a threshold into immortality, becoming one of the most famous disappearances in American literary history.

And it wasn’t long ago that we Heathens learned that Bierce was born in a log cabin along Horse Cave Creek in Meigs County, Ohio. Why that matters to us is because, as we type this — just outside Point Pleasant in Mason County, West Virginia, which borders Meigs — we sit a scant thirty miles from where Bierce first drew breath!

And let us tell you: having grown up here, one of the things you learn early about the five counties that border Mason is that you just don’t mess with people from Meigs — they’re built different — so it’s no surprise to us that one of the most ferocious authors who ever lived, a man capable of blisteringly vicious satire and wickedly virulent puns, was borne of Meigs County.

You ask us, that explains everything.

But back to “Owl Creek”: it was originally published in the San Francisco Examiner on Sunday, July 13, 1890, for which Bierce was a regular columnist and editorialist.

Afterward it was published with eighteen more short stories in his 1891 collection Tales of Soldiers and Civilians.

It’s hard to overstate the impact this story has had on literature and art ever since. It stands as one of the preeminent American stories, endlessly reprinted, endlessly taught, and endlessly admired, influencing and inspiring everything from novels to movies to music.

It has also been adapted several times and in many mediums, with the most faithful being the 1961 French short film La rivière du hibou, written and directed by Robert Enrico, which is notable for winning the 1963 Academy Award for Best Live Action Short Film, and being the first production featured on The Twilight Zone television series not created in-house, as creator Rod Serling recognized in his introduction of the February 28th, 1964, episode: “a presentation so special and unique that for the first time in the five years we’ve been presenting The Twilight Zone, we’re offering a film shot in France by others.”

In our estimation, what makes the film “so special and unique” is how closely it hews to Bierce’s story—his words given life, made real . . .

And it’s important to note, especially for a first‑time reader of Bierce, that this story’s realism is rooted in actual wartime practice. Bierce fought in some of the Civil War’s bloodiest engagements — Shiloh, Chickamauga, Kennesaw Mountain — and the starkness of this tale’s opening moments comes from his lived experience. Bierce had seen men hanged — summary executions by hanging were common for wartime saboteurs — so he writes not invented fiction but boots‑on‑the‑ground autobiography.

Contemporaries and later historians often remarked that Bierce’s Civil War sketches were among the least embellished accounts produced by any veteran. He wrote with a cold, almost reportorial precision; there is no sentimentality, no patriotic varnish. He despised romanticized Confederate mythology and distrusted Union heroics just as much; he viewed war as a machine that grinds illusions into dust. That’s why the opening paragraphs of “Owl Creek” read like a military deposition. Bierce isn’t glorifying the Confederacy or the Union — he’s gutting ideological self‑delusion, razing the ego’s retreat, and laying bare the enginery of death.

And we’re not wielding that verbal triptych lightly — it’s why Crane believed this story “contains everything” — long before Freud, Jung, and modern psychology, Bierce was exploring, dismantling, and reverse engineering our perception, consciousness, and subjective reality. He wasn’t just a war writer — Bierce was a proto‑psychological realist; he is a bridge between Civil War reportage and modernist fragmentation.

And to really qualify that gritty “built different” Meigs County marrow: at Kennesaw Mountain on June 23, 1864, a Confederate sharpshooter shot Bierce in the head — the musket ball fractured his temporal lobe and lodged behind his left ear, where it remained for the rest of his life.

Is it any wonder, then, that his journalism was savage, his satire corrosive? He bore a literary authority kindled from a sense that he had seen too much to lie, believed sentimentality was a form of lying, knew self‑deceit kills faster than bullets.

Said another way: his blood-soaked, bullet-to-the-skull wartime experiences taught him that illusions are dangerous, self‑mythologizing demands an existential toll, and cold reality is far harsher than all the warm bullshit fictions we attempt to convince ourselves of.

That’s some Meigs County pith through and through . . .

Now, as for the text, our only additions consist of the thirty-odd footnotes we’ve appended throughout the story for clarity, context, and commentary where necessary.

Finally, if this is your first time reading “An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge,” then we envy you.

To borrow an assessment from Kurt Vonnegut, we wish we could read this “flawless example of American genius” again for the very first time.

Then again . . .

Then again . . .

Then again . . .

Contents

Heathenry: Thoughts on the Text

“An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge“

“An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge“

Praise

“Bierce is remembered chiefly, if he is remembered at all, as the author of a magnificent Civil War story called ‘An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge.’” —The News and Observer

“The cleverness of invention in such a tale as ‘An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge’ is undeniable.” —The Philadelphia Inquirer

“I consider anybody a twerp who hasn’t read the greatest American short story, which is ‘An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge,’ by Ambrose Bierce. It isn’t remotely political. It is a flawless example of American genius.” —Kurt Vonnegut

“‘An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge.’ That story, we have long maintained, is the most perfect American short story.” —The Chattanooga News

“Anybody who thinks that, under any circumstances, one nightmare is enough, may be directed to the story called ‘An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge’ as a particularly excellent specimen.” –The Graphic

“His savagery and his cynicism repelled most readers. But no more superb stories have been written than ‘An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge.’” —The Signal

“Ambrose Bierce, that master of strange matters, is well represented by ‘An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge.’” —The Detroit Free Press

“The story ‘An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge’ is a masterpiece — few like it have ever been written . . . sufficient in itself to stamp Mr. Bierce as one of the greatest masters of the short story.” —The Tampa Tribune

Details

An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge

Heathen Short #10Published: January 14, 2026

Format: Paperback

Retail: $6.95

ISBN-13: 9798900750101

Dimensions: 8.5 x 5.5 x 0.072 inches

Weight: 1.8 oz

Cover: Matte Finish

Interior: Black & White on Cream Paper

Pages: 28 (+2 POD)

Language: English

Annotations: 35 Footnotes

Illustrations: 3

- Title Page

- Heathenry Flame

- Honorary Heathen Headshot: Ambrose Bierce

- Fiction / Historical / 19th Century / American Civil War Era

- Fiction / Psychological

- Fiction / Visionary & Metaphysical

The Heathen Newsletter

Want to be kept in the loop about new Heathen Editions, receive discounts and random cat photos, and unwillingly partake in other tomfoolery? Subscribe to our newsletter! We promise we won’t harass you – much. Also, we require your first name so that we can personalize your emails. ❤️

@heatheneditions #heathenedition

Copyright © 2026 Heathen Creative, LLC. All rights reserved.